A Journal of Latin American Criticism & Theory

Vol. 3, No. 2 (2024)

In this issue of FORMA, Tavid Mulder brings readers a collection of essays analyzing the autonomy of art in twentieth-century Latin America. The issue features essays analyzing literature, photography, and architecture ranging from Juan O’Gorman, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Paul Strand, and Edward Weston to Jorge Luis Borges, the “Manifesto Antropófago,” and São Paulo’s Semana de Arte Moderna 1922. The issue also includes new translations of essays by José Carlos Mariátegui.

100 Years of Autonomy in Latin America

Contemporary Latin American literary criticism often alludes to the first half of the twentieth century as a foil for its diagnoses: as the moment in which the autonomy of art was taken for granted; as a situation in which art still possessed a critical power; as a conjuncture in which literature expresses the ambitions of modernization. As the contributions to this special issue of FORMA demonstrate in compelling detail, if we more explicitly engage with the period in question, a richer picture of these dynamics and of unexpected contradictions can be drawn.

Anthropophagia and Those Twenties in Brazil: Good Old Days or Bad New Ones?

One of the problems that emerges from the impulse to reduce manifestos to their programmatic function in modernism is the resulting tendency to disregard their status as an avant-garde genre in their own right. This is the reason why Oswald de Andrade has generally been received as the great provocateur of Brazilian modernism and as an undisciplined prankster, as if all we had before us was mere propaganda for the modernist movement. It is true that there are associations between the avant-garde and propaganda, which are complex. But many critics have simply concluded that Oswald lacked any systematic formulation, in contrast to Mário de Andrade, who had developed a more cohesive artistic program within Brazilian modernism. However, is systematic formulation a relevant category for the “isms?” Do we generally level these critiques at Dadaism or Surrealism? Is it not the case that provocation is a key element of the manifesto as genre? Is it not the case that it is precisely through provocation that politics and art maintain their interaction within avant-garde movements? When we see the “Manifesto Antropófago” as a specific figuration of a transnationally constructed genre and Anthropophagia as an “ism” in which Mário de Andrade, Tarsila, and many others would be included, we open up a new perspective on it.

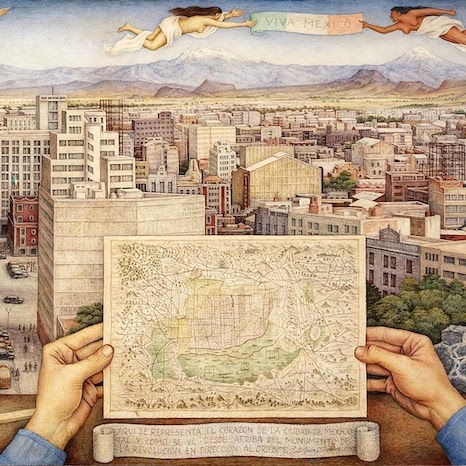

The Prolific Roads of Reedification: Literature, Architecture, and Autonomy in Post-Revolutionary Mexico

In post-revolutionary Mexico, the metaphor of reedification offers a peculiar contestation to the essentialization of unmaking as the ultimate vitalist gesture, for it communicates, at some very basic level, the mundane necessity of imagining structures for holding things together. And as Caroline Levine has argued, “Things take forms, and forms organize things.” Perhaps with obvious translucency—since no other art is as immanently purposeful—the historical conjuncture of the Mexican 1930s finds in architecture a practical model to dispute the literary averseness toward social edification, i.e. to conceive of structuration as a social necessity rather than as an administered limitation.

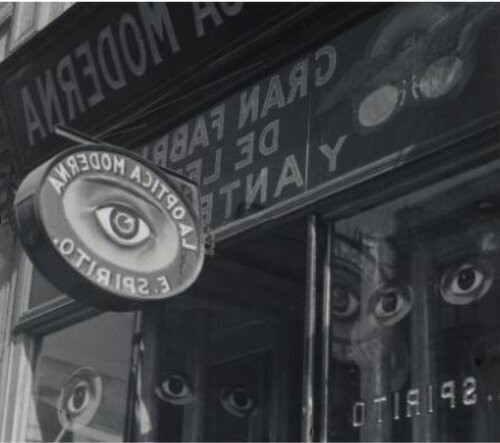

The “Go-For-Broke Game of History:” Modernist Photography in Mexico

The modernists acknowledge the indexicality of the camera, but they also suspend this indexicality by composing the picture to express the truth of the object, a truth that cannot be reduced to immediate appearances. In other words, the modernists attempt to defeat what we conventionally regard as “photographic truth” in order to assert the truth of mediation. Accordingly, the modernists reconceive objectivity as inseparable from intentionality. Contrary to the presumption that intentionality exists “in the mind,” modernist photography insists that intentionality exists only when it is objective, when it assumes a material realization to which it, nonetheless, cannot be reduced. And if intentionality must be objective, it cannot be conceived as merely subjective or private; it is necessarily public, and thus, shareable with others.

Borges as Realist

“Funes the Memorious” is frequently considered to be one of Borges’s most brilliant and, ironically or not, one of his most memorable fictions. It is, by my lights, his single most consummately and artistically realized story and an indisputable masterpiece of the genre, surely one of the most stunning and nearly flawless short fictions ever written. Replete with echoes of classic nineteenth century and Victorian precursors—those of Poe and Stevenson seem all but audible in “Funes”— it nevertheless seems impossible for it to have been written in that century or, indeed, much before it was, in the 1940s. Funes emerges out of a remarkably rich and meticulously assembled matrix of realistic detail, simultaneously regional, cultural and historical. Together these constitute more than just the brush strokes of a criollismo intent on adding some regional flavor and local color. They give every indication, rather, of flowing from both an intimate and a broadly sweeping knowledge of regional geography, culture and history itself, albeit here only sparingly and casually deployed—as it were, metonymically— by the narrative.

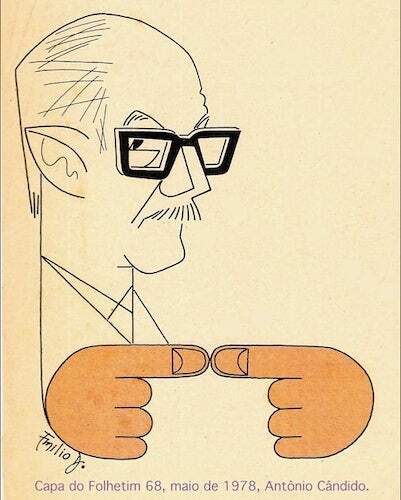

The Two-Step Formation Model of Ángel Rama and Antonio Candido: Late Modernism and Aesthetic Autonomy

Like few other places, Latin America has writers whose claims to literary autonomy have revealed interesting tensions for understanding a complex and conflicting historical process of global and local modernization. Renewing the discussion about this process (both literary and historical) may perhaps allow new understandings of Latin American New Narrative as a fascinating and contradictory case of late modernism, in a context in which concepts such as "development" and "modernization" already seem anachronistic, and in which contemporary critics and writers of different orientations tend to discard the notion of autonomy altogether, without fully understanding its complexities and the critical contents it was able to express during our crucial developmentalist period.

“Autonomy of art, yes; but not the closure of art:” José Carlos Mariátegui on Modernism and the Avant-Gardes

The death of the old realism has not prejudiced us absolutely against knowledge of reality. Instead, it has facilitated it. It has liberated us from the dogmas and prejudices that had constrained our knowledge. Sometimes, there is more truth and humanity in the implausible than in the plausible.